Constitutional Court in Jackson Ntwatwa v Attorney General Clarifies Jurisdiction Over Interlocutory Applications

The ruling came in the case of Ntwatwa Jackson v Attorney General (Constitutional Petition No. 9 of 2017), delivered by a reconstituted panel of five Justices on Wednesday

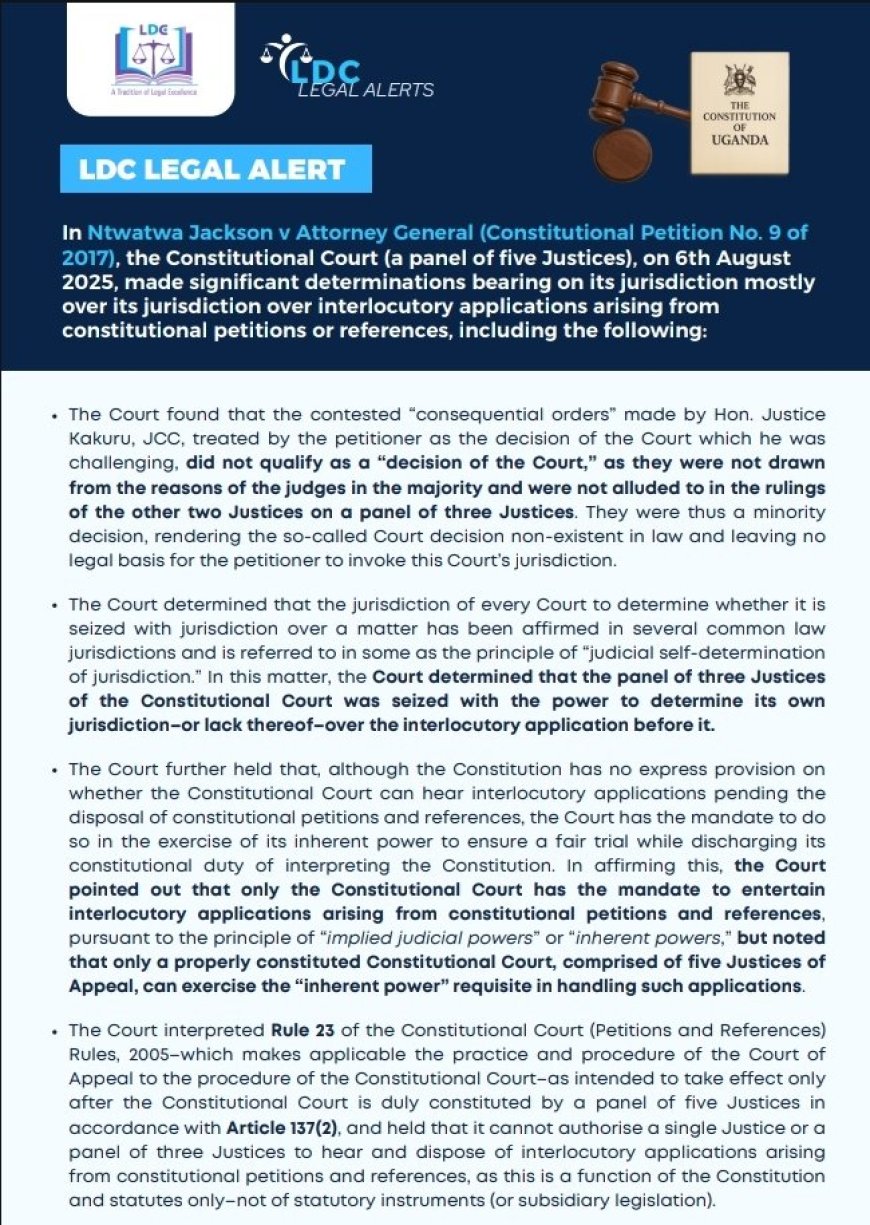

In a landmark decision that redefines the boundaries of its jurisdiction, the Constitutional Court of Uganda has clarified that only a properly constituted panel of five Justices can entertain interlocutory applications arising from constitutional petitions and references. The ruling came in the case of Ntwatwa Jackson v Attorney General (Constitutional Petition No. 9 of 2017), delivered by a reconstituted panel of five Justices on Wednesday August 6, 2025

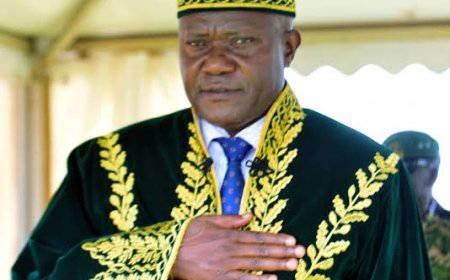

The judgment, written by Justice Muzamiru Mutangula Kibeedi and unanimously concurred in by Justices Geoffrey Kiryabwire, Cheborion Barishaki, Irene Mulyagonja, and Christopher Gashirabake, addressed key questions about the Court’s own jurisdiction and the procedural propriety of previous “consequential orders” challenged by the petitioner.

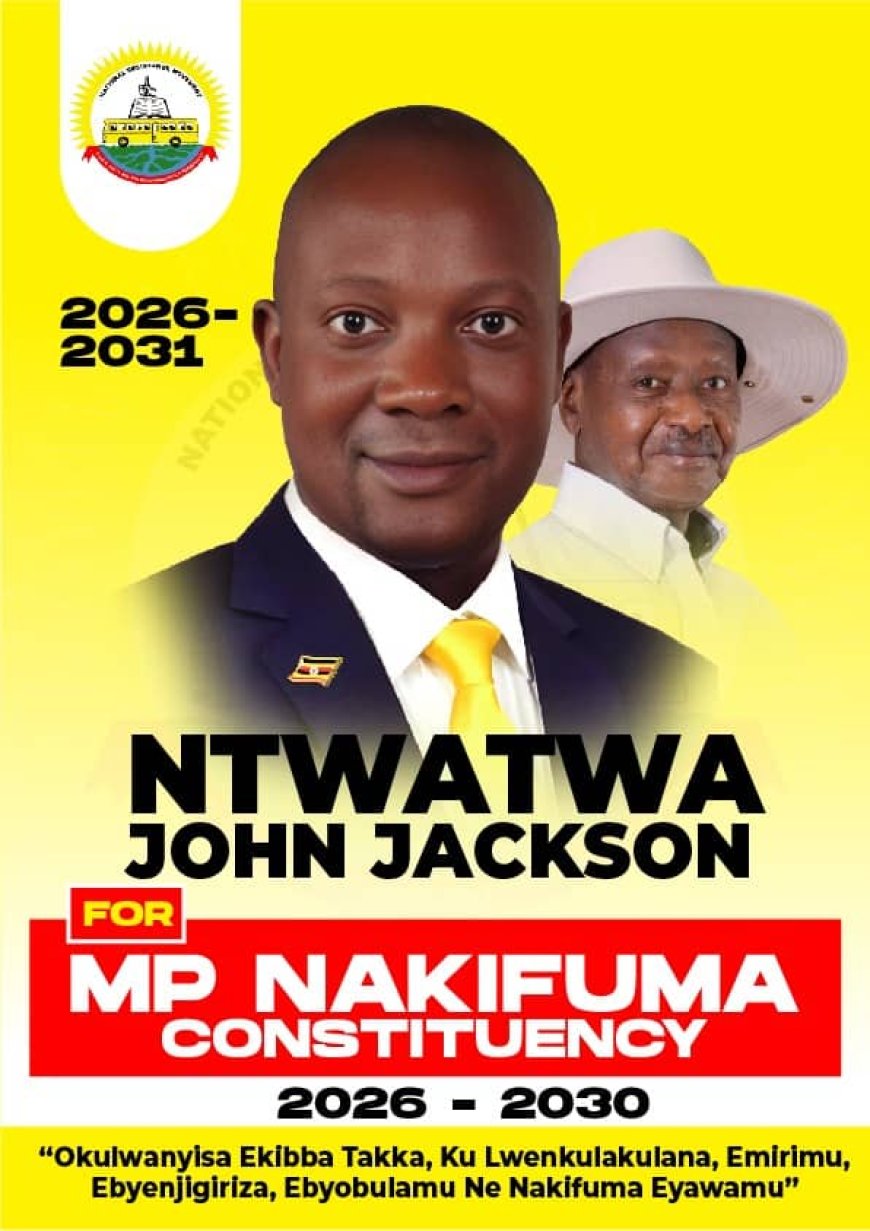

The petitioner, Ntwatwa Jackson, sought to challenge what he considered to be a decision of the Constitutional Court — “consequential orders” issued by Hon. Justice Kenneth Kakuru, JCC — in an interlocutory application connected to a constitutional petition. However, the Court found that these orders did not constitute a decision of the Court in law.

Justice Kibeedi observed that the orders were not drawn from the reasoning of the majority judges and were not referred to in the rulings of the other two Justices who sat on the original three-member panel. This rendered them a minority decision, legally incapable of being treated as a binding Court decision.

“The so-called decision of the Court was non-existent in law,” Justice Kibeedi wrote, “leaving no legal basis for the petitioner to invoke this Court’s jurisdiction.”

The Court emphasized the long-standing principle in common law jurisdictions that every court has the power to determine whether it is seized with jurisdiction over a matter — a principle often referred to as judicial self-determination of jurisdiction.

In this case, the original three-Justice panel of the Constitutional Court had the right to determine whether it possessed jurisdiction over the interlocutory application before it. However, the Court went further to clarify the extent and limits of its powers in such matters.

A central issue was whether the Constitutional Court could hear interlocutory applications while a petition or reference was still pending. Justice Kibeedi acknowledged that the Constitution is silent on the matter, but affirmed that the Court retains inherent powers to ensure fair trial procedures in the execution of its constitutional mandate to interpret the Constitution.

He stressed, however, that these powers can only be exercised by a properly constituted Constitutional Court — a panel of five Justices as mandated by Article 137(2) of the Constitution. This means that neither a single Justice nor a panel of three Justices has the authority to hear and dispose of interlocutory applications arising from constitutional petitions or references.

“The question of inherent power falls within the realm of jurisdiction,” the judgment stated. “Jurisdiction cannot be conferred by subsidiary legislation.”

The Court examined Rule 23 of the Constitutional Court (Petitions and References) Rules, 2005, which applies the practice and procedure of the Court of Appeal to the Constitutional Court. Justice Kibeedi made it clear that, being part of a statutory instrument under the Judicature Act, Rule 23 cannot widen jurisdiction beyond what the Constitution or statutes explicitly provide.

Rule 23, the Court held, only takes effect after the Constitutional Court is properly constituted with five Justices. It cannot authorize a smaller panel or single Justice to entertain interlocutory matters in constitutional petitions and references.

This decision is expected to have far-reaching implications for constitutional litigation in Uganda. By underscoring that jurisdiction flows strictly from the Constitution and statutes — not from rules of procedure or subsidiary legislation — the Court has reaffirmed the primacy of constitutional provisions in governing judicial authority.

The ruling also effectively limits the handling of interlocutory applications in constitutional matters to full panels, a measure likely to affect case scheduling, resource allocation, and procedural timelines in the Constitutional Court.

Legal analysts note that the decision strengthens judicial discipline by preventing panels of less than five Justices from making rulings that could later be deemed ultra vires. It also safeguards the integrity of constitutional interpretation by ensuring that such matters are always decided by a fully constituted bench.